|

.jpg) Patricia: A mutual friend of ours once said to me: “Your life is a triumph of art over circumstance.” Most friends know that I grew up with trauma as the background noise. Today I realized that the awareness that came out of that is my superpower. Psychologists and books about trauma teach us that traumatized kids notice everything. They have to prepare for shocks and surprises. I became the kind of kid, and then writer, “on whom nothing is lost.” Isn’t that Henry James? Patricia: A mutual friend of ours once said to me: “Your life is a triumph of art over circumstance.” Most friends know that I grew up with trauma as the background noise. Today I realized that the awareness that came out of that is my superpower. Psychologists and books about trauma teach us that traumatized kids notice everything. They have to prepare for shocks and surprises. I became the kind of kid, and then writer, “on whom nothing is lost.” Isn’t that Henry James?

So, Rob, what is your superpower or a strength that was possibly engrained in you before you leaned into writing?

Photo credit: Linda Rogers Rob: From an early age I was fond of gazing at people and things. I invented scenarios in my head to explain who that person is, why they are wherever they are, and what they’re doing. I made little hand-drawn books and magazines, what would now be called Zines. I recorded 30-minute radio shows for a made-up station, complete with news broadcasts and then I’d insert a few Beatles songs.

I was that kid in high school who secretly treasured every book we read. I was lucky. I had high school teachers who assigned unconventional books like Thomas Hardy’s The Mayor of Casterbridge. We read Great Expectations, The Scarlet Letter and Animal Farm. Reading and analyzing a text seemed “easy” to me and that’s why, when I initially arrived at college, I wrote off the possibility of being an English major. I studied economics and political science for a year before waking up and realizing where I belonged.

When I took my first creative writing class, I felt at home in a way I’d never felt in a classroom. I suppose that is why I never left it. I don’t know if any of that has anything to do with a “superpower,” but I know that I was drawn to narrative, storytelling, and literature in a way that felt deeply rooted in my being. Almost like it’s part of my genetic blueprint.

Persistence or diligence are probably the superpowers that get me through much of the work I do. I am always thinking about the next project. I take a little break after I finish a book and let the fields lay fallow, but not for long. I try to work 5-6 days a week and have for over 30 years. Showing up and getting busy: is that a superpower? Or just an obsession.

Patricia: So you were born with innate curiosity that didn’t get squelched. And persistence and showing up is how the work gets done. It makes me a little sad to hear younger writers (who have big dreams) say that they don’t think it’s necessary to have a regular practice. That’s how you gain mastery, in my opinion.

Rob: I think you’re right, but then I was talking with the poet Diana Khoi Nguyen. We were talking about her second collection, Root Fractures. She told me that she hadn’t worked for months. Ideas were percolating. When she finally sat down to write, she produced the entire book in something like six weeks. And it’s very good!

I think the creative process is mysterious. Probably unique for each one of us. I know that, for me, to be in the chair every day is the right place. Like Eliot’s “well oiled machine.” If you are there and your tools are sharp and at the ready, you’ll make the most of the good stuff when it shows up.

Patricia: I shouldn’t be so critical. To each her own process. Of course, I take time off. So when students ask if I write every day, I usually say that I write every day when I am working on something. But when I first started out, it was sacrosanct to write at least five or six days a week. When Grace Paley came to Purdue, a student asked her, “What do you do when you can’t write?” And Grace said, “I visit my sister.” And that is one of the best things about writing short stories. You can let go for a while in between stories. Writing a novel is a totally absorbing experience. To write my novels I had to keep after them obsessively. I was afraid I’d lose the thread, the passion for the project.

Rob: I love that Paley anecdote! Time off after a major project isn’t merely “not working.” It’s recharging, building up energy for the next project. I understand now that, for me, it’s a vital part of the larger cycle. Rob: I love that Paley anecdote! Time off after a major project isn’t merely “not working.” It’s recharging, building up energy for the next project. I understand now that, for me, it’s a vital part of the larger cycle.

But your other point, establishing a regular writing practice, is so vital–especially for beginning writers. Flannery O’Connor talks about “the habit of art.” That can entail many things. Certainly a work ethic and a commitment to doing that work is part of it, at least for me.

Patricia: And look at your body of work. It’s impressive because you are persistent.

Rob: Just keep showing up and doing the work! It’s funny: at the end of every teaching semester I have a little freak out. “Oh, I didn’t get enough writing done. I wasted this time.” Then I tally up all the draft pages I worked on and, almost every time, I am surprised. I got more work done than I thought.

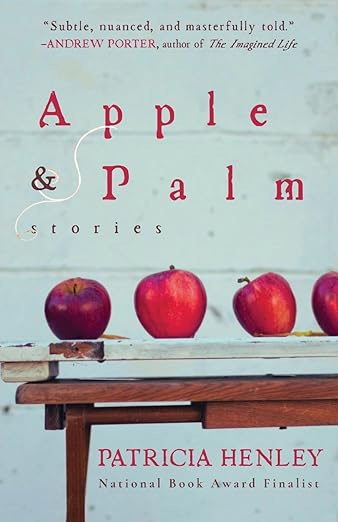

But let’s think about your work. Apple and Palm is a collection of linked stories. A character mentioned in one story might be a protagonist in the next. Storylines cross over. There’s a cumulative effect for the reader, a fruitful compounding of meaning. Did you conceive of this approach from the start of the project, or did it emerge during the writing?

Patricia: If only I were that organized. I wrote these stories under duress. The pandemic. My cancer diagnosis. My beloved dogs dying. Selling my house and moving across the country. I wrote them one by one, as stand alone pieces, but I liked the characters. It became obvious after the first several stories that it was a good vein to mine. Good, in the sense that I enjoyed writing about this particular place and these characters.

And I’m interested in rural places and how, as Barry Lopez wrote, landscape shapes mindscape. The vibe in small communities interests me. I’m curious about how lives overlap and the nodules of connectedness.

That brings to mind the question of place. Do you gravitate to writing about certain places? You’ve lived in several places. What makes a place appeal to you as fodder for your writing?

Rob: Certain places hold a powerful spell over me. Minnesota, where I grew up and spent my early adulthood. There are several stories set there. My novella “Infidels,” in What Some Would Call Lies, is a sort of love letter to the Duluth of my childhood.

Any place where I live long enough to know it on an intimate level inevitably presents itself as a setting. I’ve written stories set in Texas, Indiana, the Eastern Caribbean, and Taiwan. I’ve now lived in Northern California for 20+ years. That is the longest stretch of time I’ve stayed in one place. And I love writing about it.

Place means much more to me than a geographical location. It is a spirit, a sensibility, an ethos. Leaning into that as a fiction writer is one of the most exciting things for me.

Patricia: And do your students, in 2025, have well-developed senses of place, places they feel an affinity for?

Rob: Definitely some do. I live and work in Northern California, very near the town of Paradise, the town that was decimated by the Camp Fire in 2018. Eighty-four lives were lost.

I remember some stories that came into my fiction workshop after that–stories from students whose family members had perished. Students who were currently homeless, living in their cars, because they’d lost their homes. Those writers captured that small town, rural vibe–and of course the terror and the ongoing consequences of that disaster and how it changed everyone’s lives. It was a powerful teaching moment for me, to be with them through all of that.

Patricia, you’ve lived and worked in many different areas. Your sense of place is extraordinary. I think of the Montana stories in your first book, or the Maryland of Apple and Palm. How quickly do you pick up on the vibe of a place? When does it speak to you as a writer? Does it ever fail to do so?

Patricia: I live a rather solitary life and have been a lifelong walker. I automatically take notice of people, details of the season, work and industry, and so on. Curiosity drives me. Spending too much time with others can sometimes get in the way of noticing what is peculiar or delightful about a new place. Does seeking an affinity with place ever fail me? I’ve lived in a few places that I haven’t written about. Yet –!

Rob: I admire how Apple and Palm acknowledges a variety of sexual orientations and a diversity of gender identities. Can you talk a bit about how you decided to approach these issues in the stories? Why do you feel it’s important to recognize this diversity?

Patricia: Sexual orientation and diversity of gender identities used to be so hush-hush. I knew my mother had been known as a tom-boy as a girl. The priest at my church was rumored to be gay. One of my best friends in high school was gay and revealed that to me. He couldn’t help himself because we both had a crush on the same teacher. I was always curious about these undercurrents. It has been such a relief for questions of identity and sexual orientation to become something we can name and discuss and live out. This has shown up in some of my earlier work, but it’s seldom mentioned. In Hummingbird House Kate is attracted to her longtime woman friend. The implication is that she is bi. In In the River Sweet, a hate crime against the LGBTQ community is at the heart of a subplot. Why is it important? I feel a need to keep saying, They live among us, even though I am not of that demographic. One thing that irks me is the way many people my age can’t handle the presence of trans folks. It pushes their buttons. Trans folks being out forces us to acknowledge that there are many ways of being human.

Rob: That’s an important social value of literature: to give a face to those sometimes overlooked, invisible people. To humanize them on the page, because society sometimes fails to do so in real life.

Patricia: I think it was the Irish writer Frank O’Connor who said that short story writers give voice to submerged population groups.

Let’s talk about the psychology of writers. In A Swim in the Pond in the Rain George Saunders writes: “The writer may turn out to bear little resemblance to the writer we dreamed of being. She is born, it turns out, for better or worse, out of that which we really are, the tendencies we’ve been trying all these years, in our writing and maybe even in our lives, to suppress or deny or correct, the parts of ourselves about which we might even feel a little ashamed.”

Is this notion something that speaks to you? If so, how have you seen a progression away from the writer you dreamed of being to the writer you are?

In some ways this brings to mind Stephen Cope in YOGA AND THE QUEST FOR THE TRUE SELF. He posits that when we are young we are very involved in the Identity Project, building a sense of self with which to successfully navigate the world. Cope says that at some point, if you are evolving, or individuating, you become more interested in what he calls the Reality Project, what is.

Rob: I loved that George Saunders book. He makes me want to read all those old Russian writers again. And there are some great writing exercises I’ve lifted from it, too.

The writer one becomes–that’s an interesting and complex question. I’m currently drafting essays, memoirs, about that young writer who was also a Peace Corps Volunteer living overseas. An ardent aspirant, but not particularly wise or experienced. Those ten thousand hours of labor are humbling but instructive if you remain attentive. One failed start after another for a long, long time… until one day you have something you want to keep working on. Then the first one gets published. The next phase of the journey begins.

In one sense, the writer who finished Welcome Back to the World (2024) has been on a long campaign to write the best pieces of character-driven social realism that he can, and he’s been at it since the 1980s. But I keep trying to surprise myself.

Out of the work I’ve managed to publish—five books of short fiction–the book that surprised me the most was my collection of flash fiction, Spectators (2017). I honestly didn’t see that one coming. I was working on a novel (as yet unpublished) and hit a wall. I needed to do something different. I was invited to do a gallery show with a photographer whose work I admire, Tom Patton. I wrote three or four flash fiction pieces in response to his work. At the gallery, we hung broadsides of my fictions next to his color photographs. That show was a success, but I had been bitten by the bug and ended up writing forty-two pieces in response to Patton’s work. And then other visual artists & writers. Eventually I had a book!

I had a lot of fun with it, creating rules for myself: nothing over a page; more lyric and less narrative; eschew conflict and character; aim for music, music, music. I’m glad I wrote that book and surprised myself. The college student starting out in 1985 never would have imagined a book like that.

Patricia: One thing I love about the writing life is that we never know what we’ll become obsessed within a year or five years.

Rob: Aging, desire, and the body are key themes in many of the stories in Apple and Palm. Nothing is clean-cut or predictable in this regard. The lives of these characters are suitably messy. Can you talk about the older characters in the book and what you hope the reader takes from these stories?

Patricia: I’ve been influenced by a book by a Jungian analyst — Jean Shinoda Bolen — titled Goddesses in Older Women: Archetypes in Women Over Fifty. She writes about the juicy crone phase that many older women enter. They are done with child-rearing and often done with devoting themselves to the growth of others. They have choices to make. And the important thing is that they recognize that they have choices. Not all of my women characters making choices are over fifty. But they do make choices that may seem unconventional. They have entered the phase of not caring what others think. The men in the stories are somewhat peripheral; I hope their characters come alive on the page.

Patricia: When writers give public readings and do Q & A, it’s not unusual to be asked, Where do your stories come from? I’m thinking a lot about this right now because I’m writing about the evolution of my story “Currency.” But this might be true of most of my stories. I have a kernel of some sort, a place or a character in a particular situation. I start riffing on that and enter what I’ve heard called “the writing trance” or “the vortex.” I build the story – at least the first draft or so – without trying to be rational about it. The next step is sorting out some answers to interrogations, such as, how many scenes does it take to tell this story, and how do I escalate the tension? Finally, after the story is finished, something might become obvious about the story that I didn’t see when I was in the vortex. It might turn out to be “about” an old favorite theme. Or it might reveal itself as something new that I’m obsessed with. I’m thinking of this now as the secret spring, the source of the story I finally told.

Does any of this sound familiar to you in your own process? Or – what is your process?

Rob: Our processes sound very similar, and we probably talked about that when you were my mentor at Purdue in the Nineties. Writers like Flannery O’Connor, in her essay “Writing Short Stories,” or Raymond Carver, in “On Writing,” confirm for me that it’s okay to sit down with a germ of an idea and explore. I have always employed an “organic” method of composition, which is to say I don’t plot out much in advance and rarely have an idea of an ending. I have an image, a place in mind, a character or a fragment of dialogue, and I begin. I write blind, making it up as I go.

My first drafts, written by hand, tend to be expansive messes, full of left turns and dead ends. In that phase, I am the dreaming artist. I don’t worry if any of it makes sense or means anything. I’ll make it make sense later, in revision.

Patricia: Do you have an awareness of interrogating your stories, in order to discover what you really want to say? Or the best way to say it? This is a question about revision, which seems to me difficult to teach. How do you revise?

Rob: I interrogate my stories, but only when I begin to get into the middle- and late-stages of revision. I am careful, during the early rounds of drafting, to remain open to the limitless possibilities of any story. This is fiction, after all.

I am a slow, patient reviser who goes over things multiple times. With each pass I try to answer or resolve the remaining questions and concerns in a story—an interrogation of a sort. At a certain point, I find the story starts telling me what it needs. The characters tell me what they need. And so, with each subsequent draft, doors begin to close. Certain choices on the page begin to feel inevitable given the characters, the lines of tension, the scenes, or the sentences (tone, rhythm). Getting a new story across the finish line always feels like a major campaign has been fought and won.

That’s the secret history of every story the reader encounters. What is the end point for the writer becomes the beginning point for the reader, a beautiful process. And, in the end, the writer just becomes another reader. The story now has a life of its own.

Patricia: I like thinking of it that way.

Rob: You started out as a short story writer. But you’ve also published poetry, nonfiction, and two excellent novels. In your two most recent books, Other Heartbreaks and Apple and Palm, you’ve returned to the short story. What is the appeal of the form? Has writing stories changed for you in any way?

Patricia: I have always loved the short story. I devoured the stories of Richard Ford, Alice Munro, and William Trevor when I was first starting out. I sought out stories in The New Yorker from the early seventies onward. Right now I am enamored of the work of Tessa Hadley, and I’m re-visiting the stories of Edith Perlman. I started writing short stories partly because of their economy. Novel structure felt beyond me at that time. Now I don’t mind taking up space. My stories might have been novels. I love the process of achieving a certain density of experience in the lives of my characters, while still keeping to the confines of a short story. And, as always, like a therapist, I suppose, I’m keen to learn how the past informs the present.

What attracts you to it? And do you have plans to focus on the novel?

Rob: I’ve written two novels, both set in the Eastern Caribbean. One is a reworked version of the MFA thesis you chaired at Purdue in 1997. That novel is currently in the drawer. The other is out on an editor’s desk at the moment. That book took me thirteen years of on-again, off-again labor to complete. Honestly, I don’t know if I can do that again! But I never say never.

Patricia: It’s important to acknowledge the labor of novel writing. The first fifty pages always seem like falling in love. Then the hard work begins.

Rob: I’ve had better luck with the short stories, at least so far. I can’t say writing stories is easier, because it’s never been easy for me. I like attempting new things with each story. If there is a technical move I haven’t tried, or a genre or narrative stance that I haven’t tackled, I see that as an opportunity. “Searching for Florence” in Welcome Back to the World is a riff on the detective story; it’s also a meditation on the artistic process: how and why we write stories. Realizing I’d never written a story quite like that made me excited to complete it. I’m always seeking new challenges and the short story is an inexhaustible muse.

Rob: In her essay “Place in Fiction,” Eudora Welty writes that “Place is one of the lesser angels that watch over the racing hand of fiction.” That comment has always surprised me, given the importance of place in Welty’s work. Place is clearly important in Apple and Palm, with many of the stories set in the same small Maryland town. Can you talk about the role of place in your fiction? How important is it? Why was it important to center the book on one principal location?

Patricia: My colleague back at Purdue, Marianne Boruch, used to say, “You take what’s in your beggar’s bowl.” I landed on the edge of Appalachia to be near my siblings. It’s a beautiful, and maybe little known, part of the country. I explored it, and it crept into the micro-memoirs I was writing between 2015-2018. After settling there, it seemed natural to portray it, to honor it, because much of what I do when I write about a place is this: I reveal my delight or my sorrow.

On another topic: What are your thoughts on the current small press landscape? And Cornerstone Press, in particular?

Rob: The consolidation of New York publishing into a handful of houses–like Hachette or Random Penguin House–has produced a silver lining of sorts. The small press and indie press market in the States is thriving. There are more small, independent presses out there than ever. Part of that is because print-on-demand publishing is very affordable. And of course there is online publishing and e-books. Also, there are more niche presses: presses that publish feminist writers, or writers of color. Indie publishing is more diverse in that regard than New York. A lot of our best writers get their start there. (Some never leave! Ha ha.) It’s an exciting time for the market.

The flipside is that some presses don’t last long. Smaller presses with smaller staff often have less money for advertising, mailing out review and contest copies, and things like that. An author has to be prepared to take on a lot of the PR work for a new book.

I’ve had four different publishers for my six books. Two of them have folded for different reasons. The third no longer publishes short fiction because it is a university press and, according to the bean counters, short fiction doesn’t sell.

University press publishing has had to evolve. One of the more interesting stories in this regard is Cornerstone Press at the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point. They’ve been around for a while, but under the current director, the unstoppable Ross Tangedal, the press has expanded and is publishing an impressive number of books each year. Their list of authors is very strong and getting stronger.

It’s a teaching press, so students in literary editing & publishing classes work on each book. That might scare some writers off, but I loved it. We have a similar type of teaching press here at Chico State, Flume Press. I’m familiar with the model. One advantage is that the cost of running the press is, to some extent, folded into the normal teaching structure of a small state university. That’s very smart. As long as the students keep coming and paying tuition, you’re going to have that labor pool and costs, I imagine, are lower in that regard. The students are learning in real-time how to work with each author. It’s excellent professional experience. A win-win.

I was very satisfied with every step of the process that produced Welcome Back to the World (2024). Dr. Tangedal is very good at what he does, and runs a tight ship. I am singing their praises. And now they are bringing out your book, Apple and Palm, in 2026. I am just so happy to hear that. Cornerstone Press is a small wonder.

Patricia: Agreed! Cornerstone Press is training the small press editors and publishers of tomorrow. Ross Tangedal and his students have been a joy to work with.

Rob Davidson is the author of six books, including Welcome Back to the World: A Novella and Stories (Cornerstone Press, 2024), winner of the 2025 National Indie Excellence Award in Short Stories. He received his MFA in fiction writing from Purdue University in 1997, where he studied under Patricia Henley. He teaches creative writing and American literature at California State University, Chico. Visit www.robdavidsonauthor.net

Patricia Henley’s fifth collection of stories Apple & Palm is forthcoming in March 2026 from Cornerstone Press. She is the author of three novels, five collections of stories, two chapbooks of poetry, and a stage play. Her first novel, Hummingbird House, was a finalist for the National Book Award and The New Yorker Fiction Prize. Haywire Books published a 20th Anniversary Edition of Hummingbird House in November, 2019. Her short fiction has appeared in The Atlantic, Ploughshares, The Boston Globe Sunday Magazine, and other journals. Her first collection of stories, Friday Night at Silver Star (Graywolf), won the Montana First Book Award. Her work has been anthologized in Best American Short Stories, The Pushcart Prize Anthology, Circle of Women, The Last Best Place, and other anthologies. For 26 years she taught in the MFA Program in Creative Writing at Purdue University. She teaches a monthly Zoom workshop for women writers and lives in Kingston, Washington.

|